Identifying and Testing Social Patterns in Language

We all bring social backgrounds and identities to the ways we communicate. I use data analysis and experimental methods to uncover patterns in language that go hand-in-hand with social differences — even attitudes and ideologies.

Identifying and Testing Social Patterns in Language

We all bring social backgrounds and identities to the ways we communicate. I use data analysis and experimental methods to uncover patterns in language that go hand-in-hand with social differences: backgrounds, groups, and identities — even attitudes and ideologies.

Saying it the way “they” do

When pronouncing foreign place names or words borrowed from another language, English speakers might use a pronunciation that more closely resembles the original language’s pronunciation, or less closely resembles it.

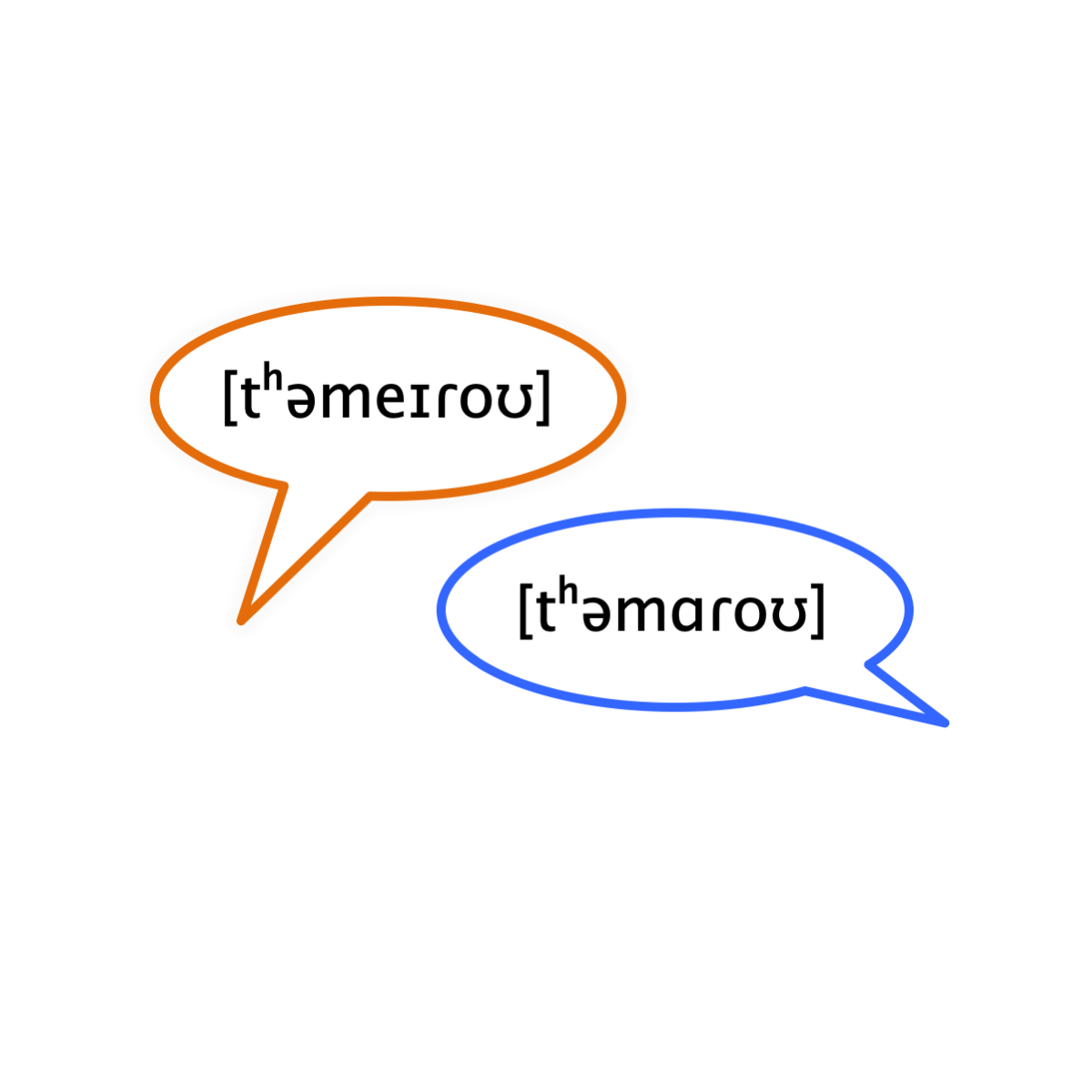

For example, the “ear-rock” pronunciation of Iraq sounds more like how it’s pronounced in Arabic than the “eye-rack” pronunciation does. I’ve found that speakers who identify with a more nationalist ideology are less likely to use a pronunciation like “ear-rock”, using a more Anglicized pronunciation like “eye-rack” instead.

So, the more you feel like people from another place or who speak another language are different from you, it seems you might be less likely to sound like them — even when saying a word from their language.

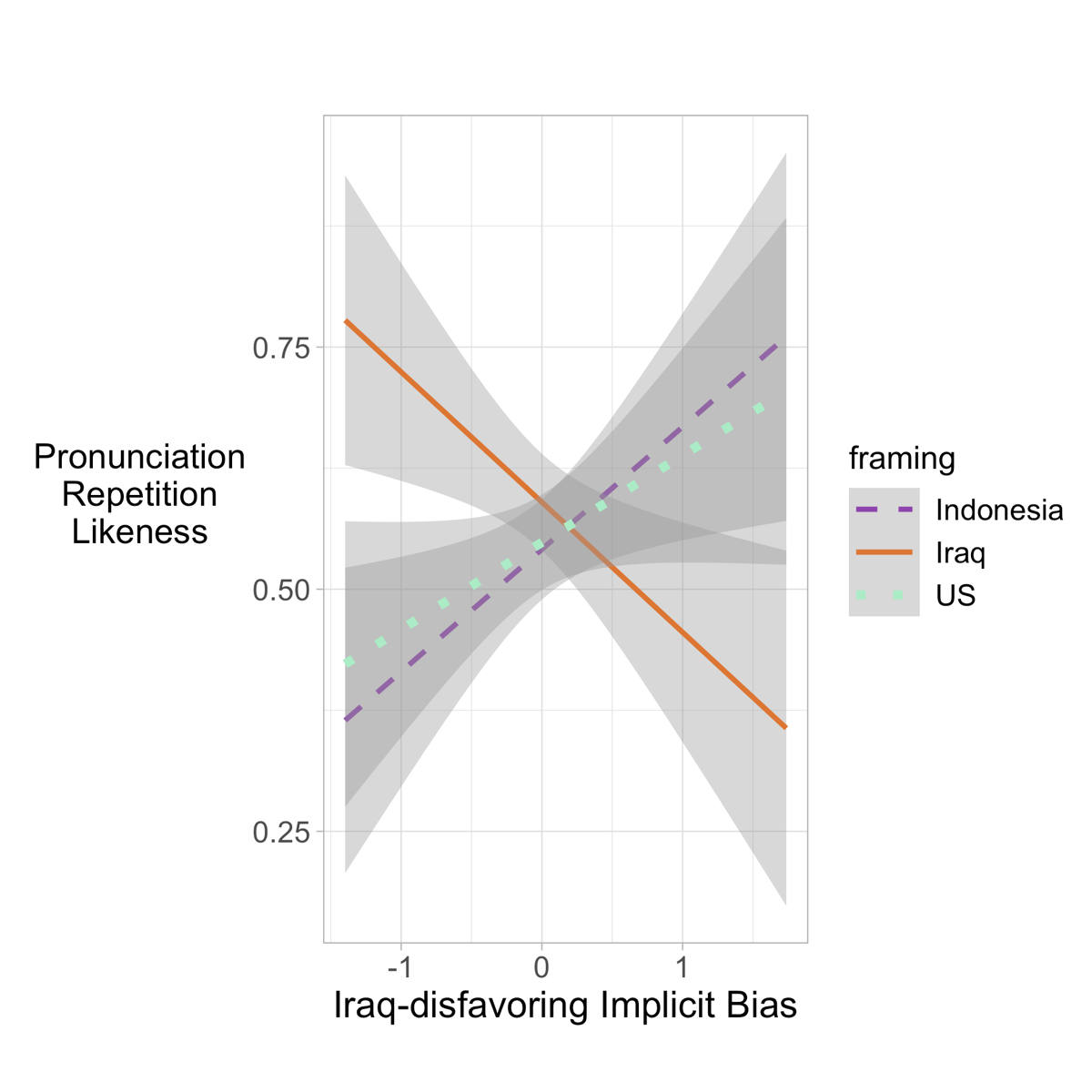

I’ve found that this pattern is broadly true for other words, too: e.g., Chile (“chee-lay” vs. “chill-ee”), spiel (“shpeel” vs. “speel”). And I’ve even found the same pattern in an experiment I designed to test how people replicated the pronunciations of new words that they heard and were led to think of as originating from another language.

I accounted for lots of social factors that might have an influence: region, political identity, language background, etc. And nationalism seemed to be the best predictor. But I also found that people’s pronunciations were influenced by their attitudes regarding the specific place or language they thought a word was from.

Here’s a short video — finalist and runner-up, “Five-Minute Linguist” — about this. I’ve also talked about it on the Tell Me Something I Don’t Know podcast (starting at 29:13) and in more depth on the Vocal Fries podcast, as well as written it up for public interest. Click here if you want to read my full dissertation for more detail.

Language varieties

Of course, there are lots of times that language differences don’t mean something like attitudes or political ideologies. Often, the language you use just reflects what you’ve been exposed to most during your life. I’ve used data analysis to look at how differences of age, ethnicity, social class, and gender show up in the way we communicate

The more we understand that everyone has an accent — a language variety — the more we can work to communicate effectively with users of all language varieties.

I also use data analysis to track and predict language change, and inform people about its social dynamics. See this journalistic piece and news interview about recent internet language trends and how they came about.